The world lost a true person of substance with the recent death of Judith Auchincloss. Judy was beautiful, deeply intelligent, warm, curious, gracious and so chic. With Julia McFarlane she was cofounder in 1976 of Manhattan Ad-Hoc Housewares, the Lexington Avenue store that brought high-tech, the industrial style for the home, to the Upper East Side. I met her socially in the early 1990s and came to know her professionally when I wrote the thesis, for my M.A degree in history of design, on high-tech. The following is a short excerpt from my thesis in which I discuss the founding of Manhattan Ad-Hoc Housewares, (complete with footnotes). I will be publishing more excerpts from my thesis in the coming year. Please check back; it was quite an opus.

New York in 1976:

Judith Auchincloss, Julia Mc Farlane

Manhattan Ad-Hoc Housewares,

Ad-Hocism and High-Tech

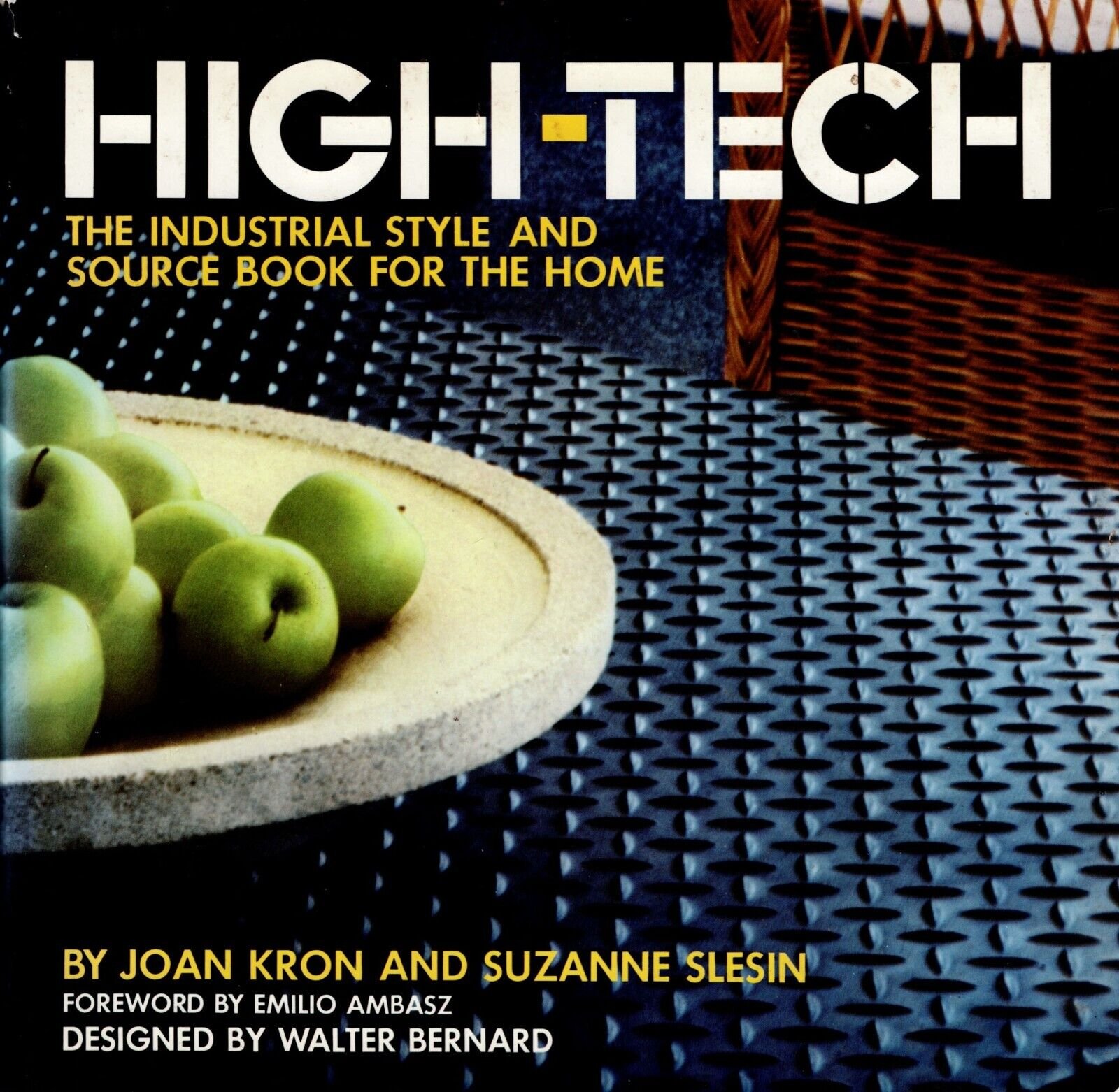

Although high-tech, the use of industrial objects and materials in the home, was an important design phenomenon in the 1970's, relatively little was written on it at the time, nor has much been written since. Joan Kron and Suzanne Slesin’s 1978 book High-Tech was the hugely influential publication that gave a name to the style, which had been expanding, like an erector set over the preceding decade. Emilio Ambasz’s foreword to High-Tech was the most accurate and thoughtful contemporary analysis of the style. Ambasz delineated a theory of high-tech in describing the work of the Castiglione brothers of Italy who, as early as the 1950's "set aside many of design's accepted academic scaffoldings and claimed that ‘finding’ and ‘choosing’ were also the object makers rightful tools ... their designs were arrived at by utilizing found objects usually recovered from the surrounding industrial landscape"1 . Thus, according to this theory, high-tech, while associated with a clearly defined "industrial" look, is not simply or exclusively an aesthetic style but also functions as a design process or conceptual gesture.

In the introduction to High-Tech, co-authors Joan Kron and Suzanne Slesin further emphasized this gestural rather than aesthetic theory of high-tech, describing the processes of recontextualization and appropriation in their explanation of "the use of utilitarian industrial equipment and materials, out of context, as home furnishings. . . . [the] appropriation of products originally created for use in warehouses, factories, battleships, hospitals, and offices."2 Kron and Slesin explained that "the myriad items of commercial and industrial equipment turning up in homes today were produced originally for utilitarian purposes, often with no thought given to style." They noted the

virtue in the fact that many of these products are well designed, although unintentionally, . . . and that they are readily available. In addition, many of these objects and materials are cheaper than comparable merchandise available through decorator sources or custom made. And when they are not cheaper they are usually more durable."3

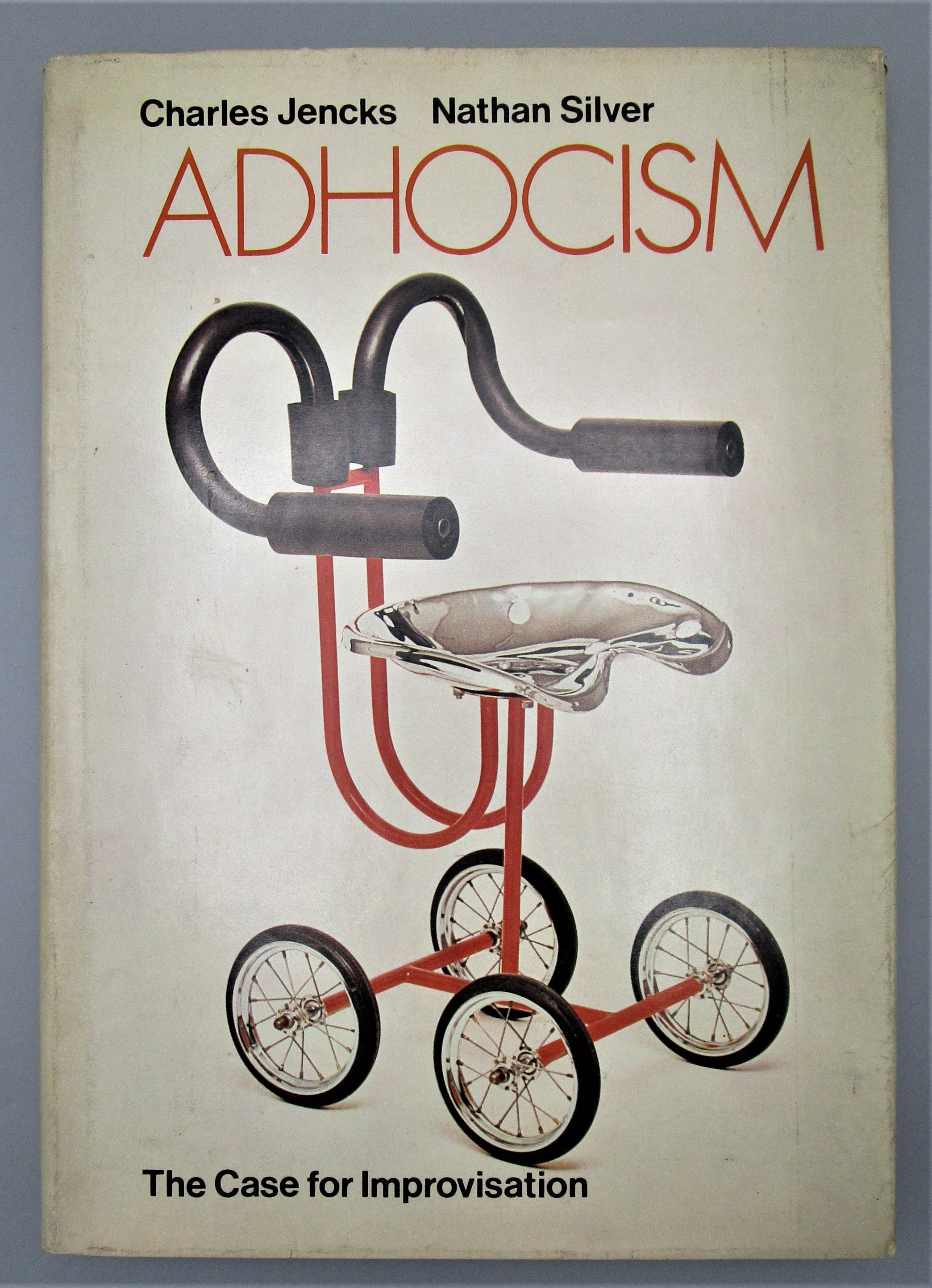

Although Kron and Slesin's book is definitive in its presentation of a high-tech design theory it was not the first publication to offer such a concept. Adhocism: The Case For Improvisation, by Charles Jencks and Nathan Silver, was published in 1972 and was a manifesto for "a method of creation relying particularly on resources which are already at hand."4 Like High-Tech, Jencks and Silver's title was the name they gave to the alternative strategy they perceived and which they advocated. Unlike High-Tech, which focused specifically on the industrial style in the home as a manifestation of an appropriationist design strategy, Adhocism was a broad ranging study that explored adhocist alternatives in urbanism, technology, transportation, consumerism, art and economics, amongst an array of categories, while presenting design as a relevant practice in each of these areas. While high-tech is adhocist, adhocism is not synonymous with high-tech. They are closely related, however, and are both part of, and exemplify, the same postmodernist practices of appropriation and recontextualization. Advocating the use of any preexisting objects or processes that solved a given problem, adhocism was a challenge to the modernist/capitalist ideology of progress that had dominated the previous one hundred years:

Today we are immersed in forces and ideas that hinder the fulfillment of human purposes; large corporations standardize and limit our choice; . . . 'modern architecture' becomes the convention for 'good taste' and an excuse to deny the plurality of actual needs. But a new mode of direct action is emerging, the rebirth of a democratic mode and style, where everyone can create his personal environment out of impersonal subsystems. . . . by combining ad hoc parts, the individual creates, sustains and transcends himself.5

Typical examples of conventional "good taste" that they cited included "Braun appliances," "French tinned copper pots," and "Scandinavian birch furniture," which they directly contrasted with "a new system of taste values permitting more devaluation of physical objects qua objects."6 In opposition to the illusory department store model of shopping "choice," Jencks and Silver proposed the compilation of a definitive index of "all products," which would be available for anyone to access. Presumably the products indexed would be necessarily functional, rather than fashionable, given the basis of the system in the demands of industry:

Why should anyone now suppose a databank would be that much better than the present hit or miss method of finding out about products through advertising, and locating dealers in the phone book or by word of mouth? The reason it seems to me such a liberating prospect is that the basic method is already being used to great advantage in the building, defense and aerospace industries, where information on products is a crucial requirement.7

Jencks and Silver proposed an extension of their exhaustive index in the form of a "supermarket for design" or a "hardware supermarket" in which there would be "no class distinctions between 'trade' and 'retail' customers nor between 'builders and architects' and 'ordinary people.'“8

Jencks and Silver's vision of a product index was partly manifested in High-Tech, which Kron and Slesin subtitled a "Source Book" and concluded with "The High-Tech Directory," an extensive listing of manufacturers and dealers of the equipment and furnishings illustrated in the earlier chapters, encouraging readers to buy direct.

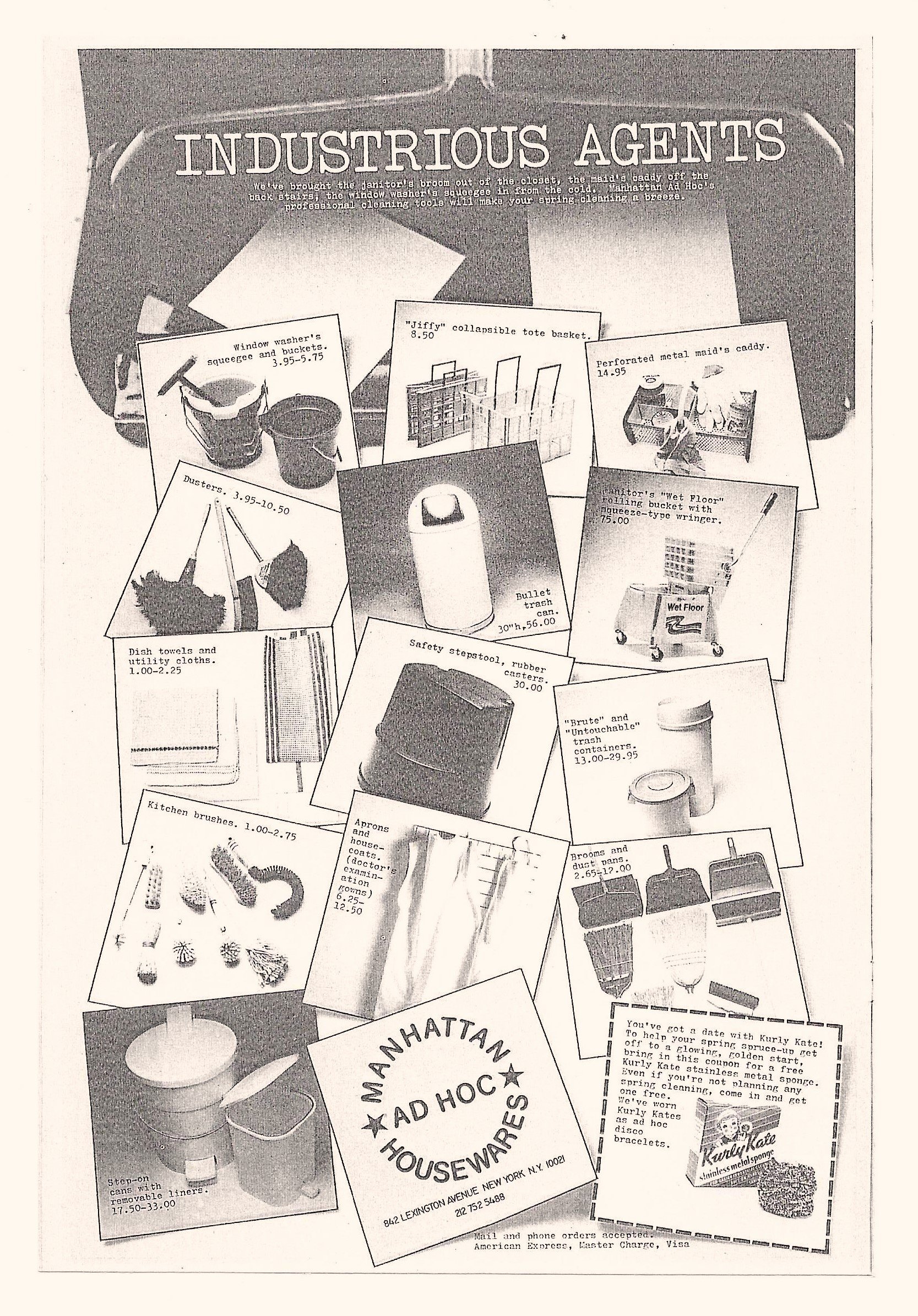

The idea of a design supermarket was partly realized in a store whose name was taken from Adhocism. Manhattan Ad Hoc Housewares was founded by Judith Auchincloss and Julia McFarlane in 1976, at Lexington Avenue at 64th Street, with the intention of presenting industrial products recontextualized for the home.

Auchincloss had been an art dealer and McFarlane had worked for Benjamin Thompson's Design Research in the 1960's. The partners had discovered the array of restaurant equipment suppliers on the Bowery, the industrial resources of the Thomas Register and the products available through commercial supply catalogues such as Sweet's Catalogue File, and determined to bring them to individual consumers by opening their "store with an idea."9 In 1979, when they published their own catalogue, just after the publication of High-Tech, they explained their attitude and inspiration:

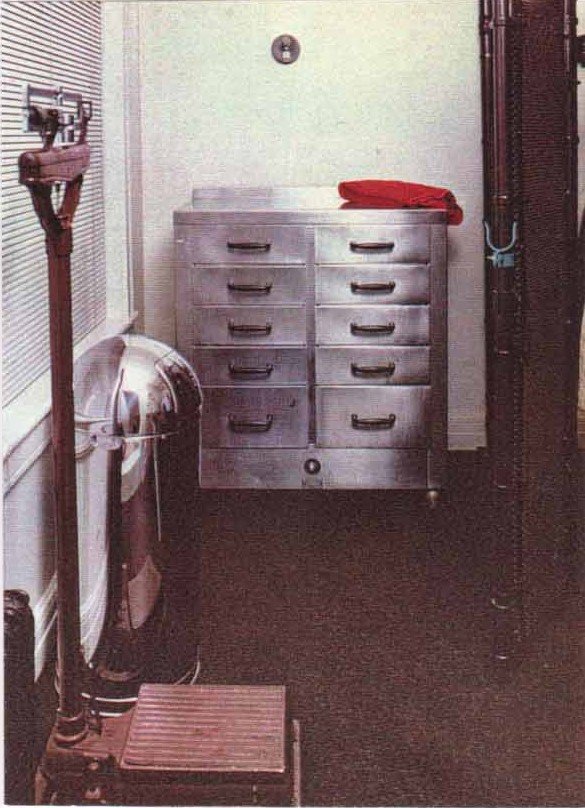

Over three years ago, we looked about and saw contradictions. Overdesigned, expensive, often pretentious products choked the market. This, at a time of skyrocketing inflation, shrinkage of living space, increasingly frenetic lifestyles. Clearly needed was simplification, clarification; . . . A book called Adhocism . . . defined our intentions. Adhocism means successful coping. . . . The adhocist becomes quick to adapt, finds pleasurable discovery in new uses for old clichés, refuses to accept limitation of choice imposed by standardized production or media imposed taste. . . . The satisfaction of being first is only heightened by being right. No more proof could be needed than the publication of High-Tech . . . Here was a masterful putting together of industrial products that reinforced our way of looking at household problems and their solutions. Need light? Try factory lamps. No place for books? Use commercial steel shelving. Flowers go where? In Kimax Laboratory glass. . . . Many of these products have been around for years. We have simply taken them out of the factory, the laboratory, the institutional building, and made them available to consumers.10

Manhattan Ad Hoc Housewares functioned as a somewhat necessary intermediary in the consumer/object hightech relationship since most of the things they made available were otherwise sold only by wholesale suppliers in large quantities. That the use of these industrial artifacts in the home constituted a radically new "look" was made clear in an article about Ad Hoc Housewares which contrasted the store's industrial offerings with the prevailing fashion for "the latest Swedish Kettle" and "teak bookshelves," remarking that "you'll be particularly happy with Ad Hoc if you are pining away in an area where everything comes in Harvest yellow and Avocado green."11 However, Ad Hoc was not simply about selling a style. Judith Auchincloss, in 1977, explained the store's perspective, which created an intellectually interactive relationship with its clients:

industrial catalogues are the backbone of our point of view. And the next most important thing, without a doubt, is an informed and intelligent customer. A person who is able to see the attractive simplicity of a laboratory beaker, who is able to transcend the limitation of thought that makes for the reaction, 'But that's not what it was meant to be used for.'12

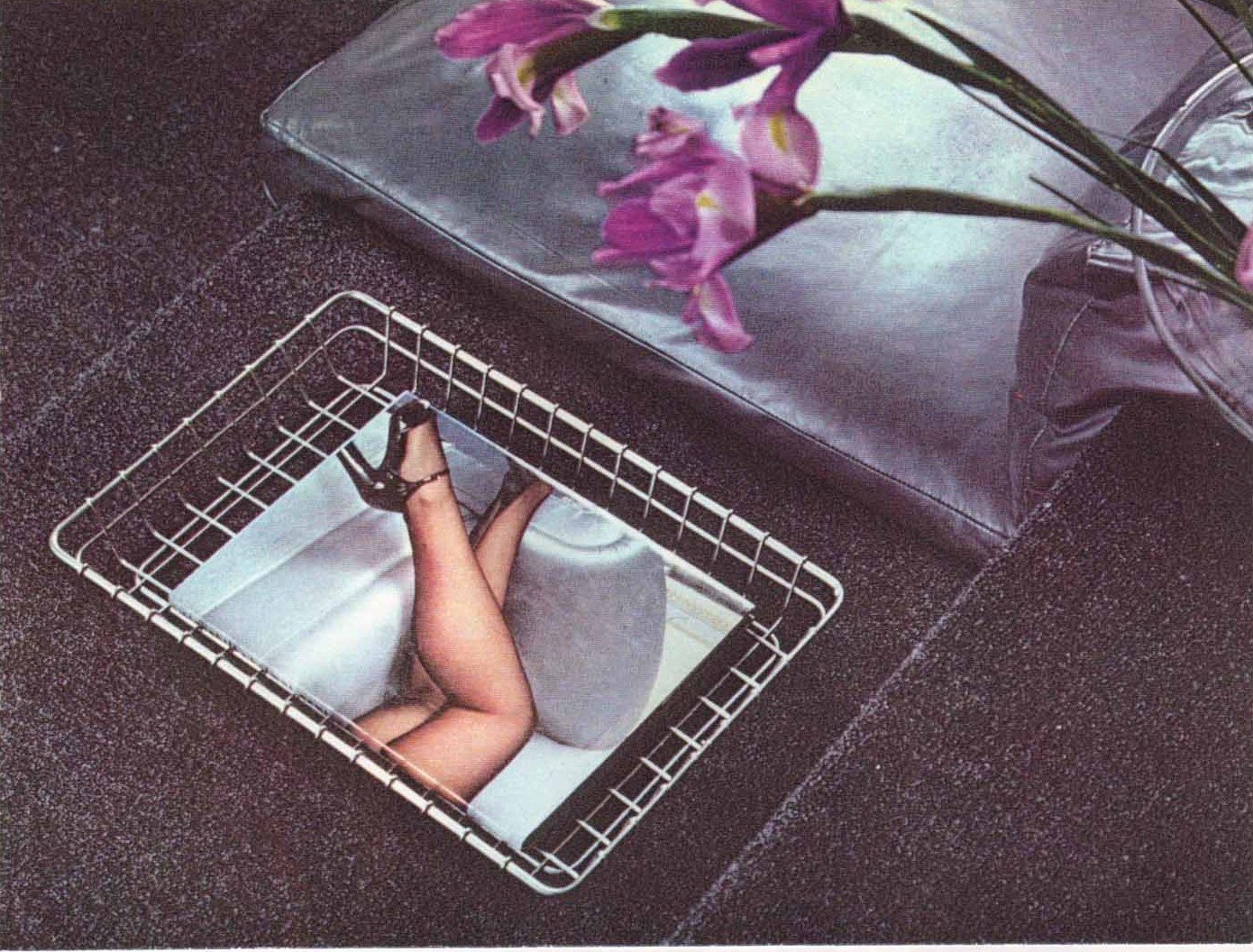

For those able to envision their domestic applications, Ad Hoc offered archetypal, iconic and anonymous objects including napkin dispensers, restaurant china, wire bakery baskets, mover's furniture blankets, and an abundance of objects appropriated from the hospital. . . . (to be continued)

Notes

1. Joan Kron and Suzanne Slesin, High-Tech: The Industrial Style and Source Book for the Home, New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., [1978], x.

2. Kron and Slesin, 1.

3. Ibid.

4. Charles Jencks and Nathan Silver, Adhocism: The Case for Improvisation, Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1972, 9.

5. Jencks and Silver, 15.

6. Jencks and Silver, 165.

7. Jencks and Silver, 175.

8. Jencks and Silver, 179.

9. Judith Auchincloss, interview by author, 6 August 1997.

10. Ad Hoc High Tech Catalog 1979-80, New York: Manhattan Ad Hoc Housewares, unpaginated.

11. "HighTechery," The Catalog of Catalogs Newsletter, January 1980, 10.

12. Peter Carlsen, "Manhattan Ad Hoc," Avenue, November 1977, 47.