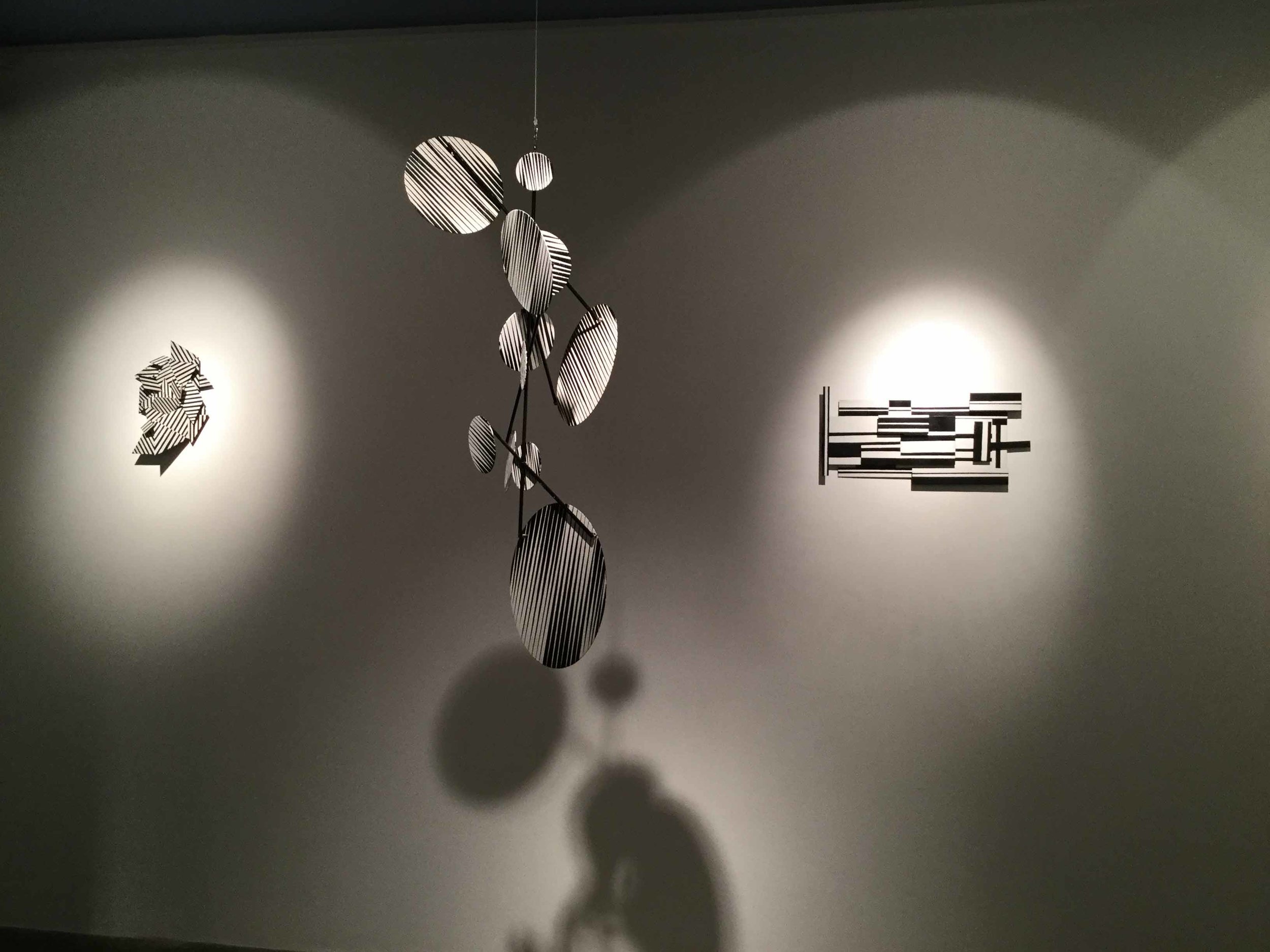

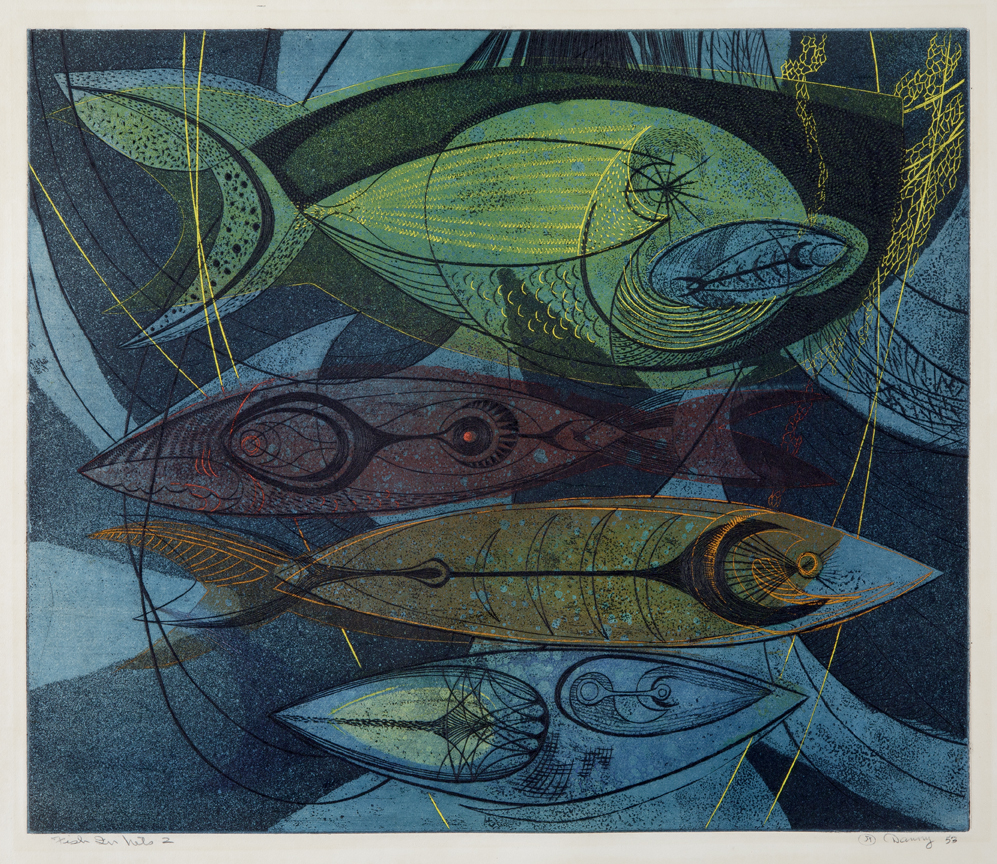

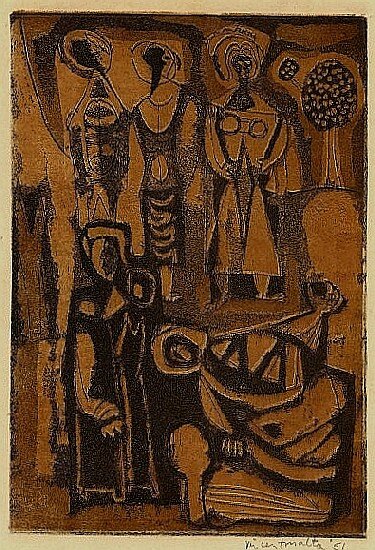

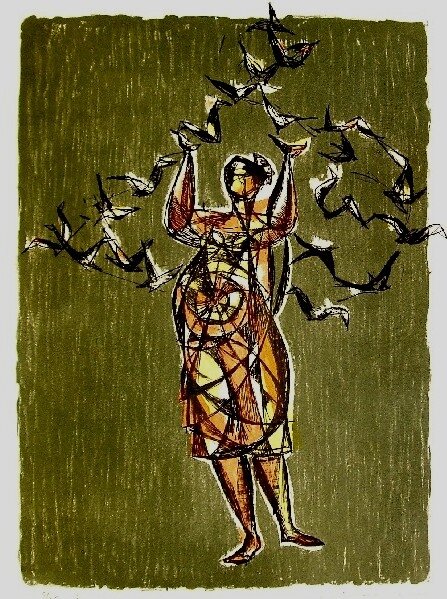

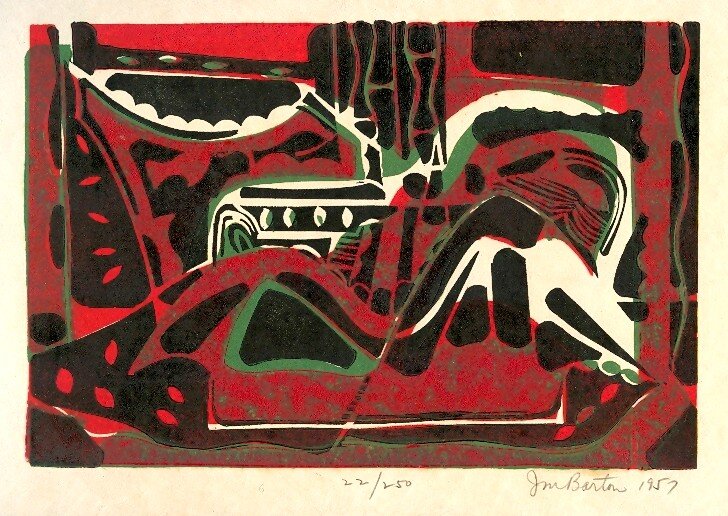

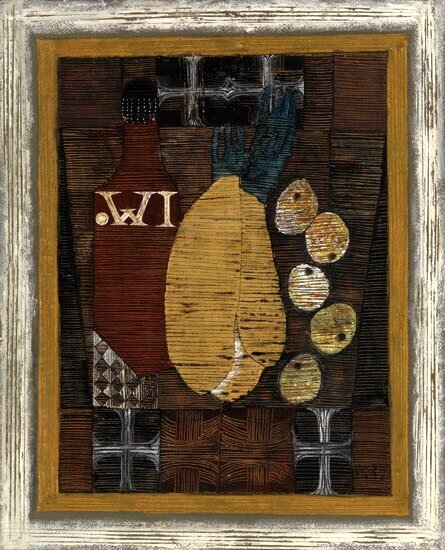

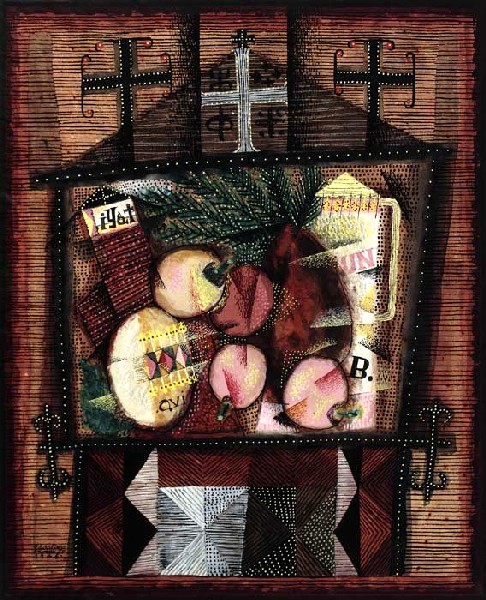

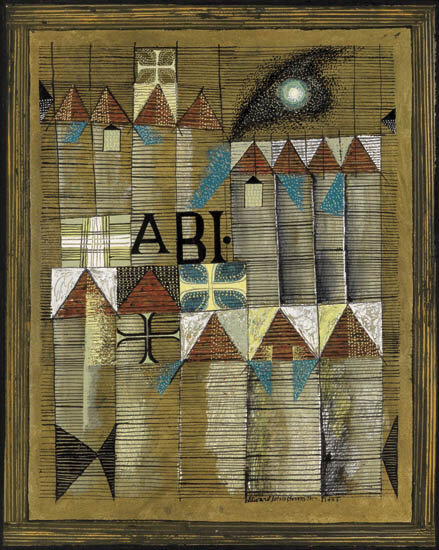

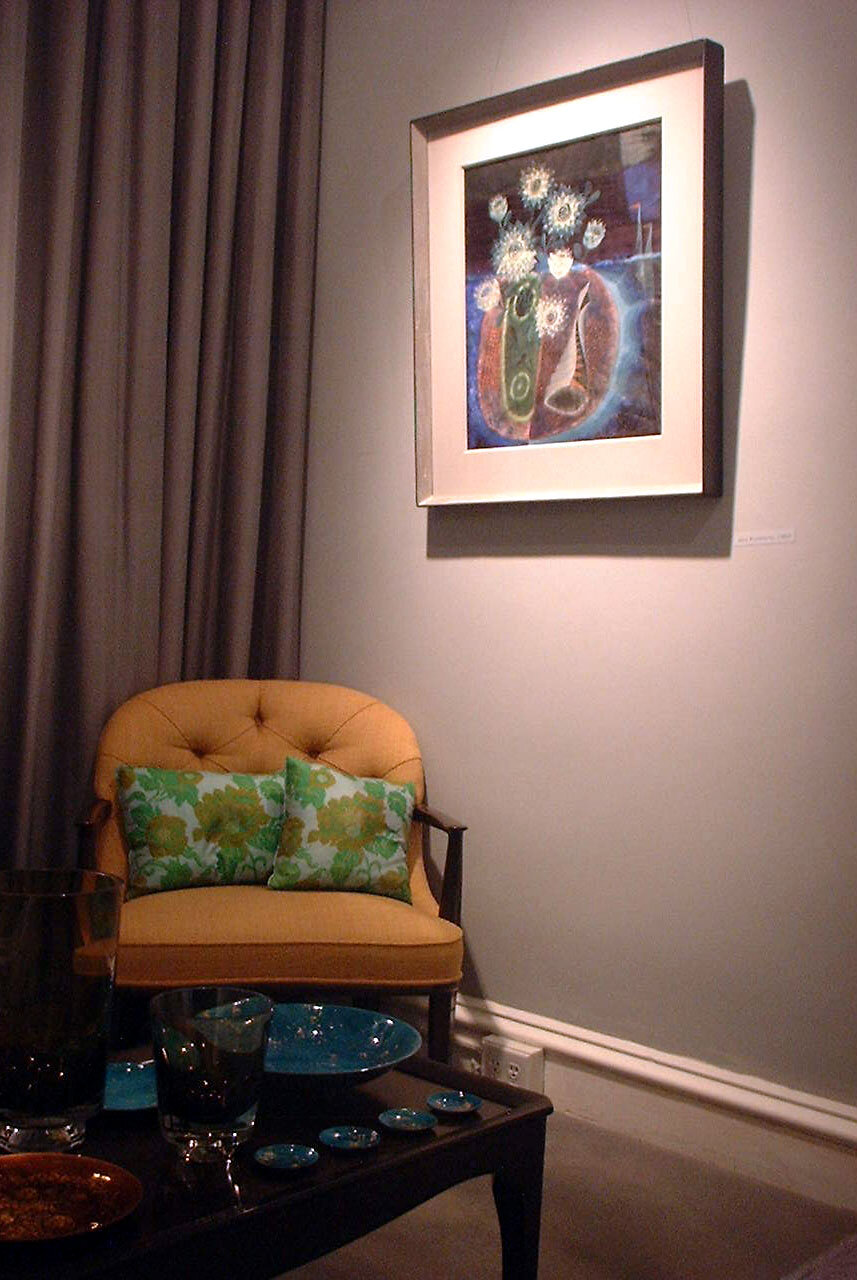

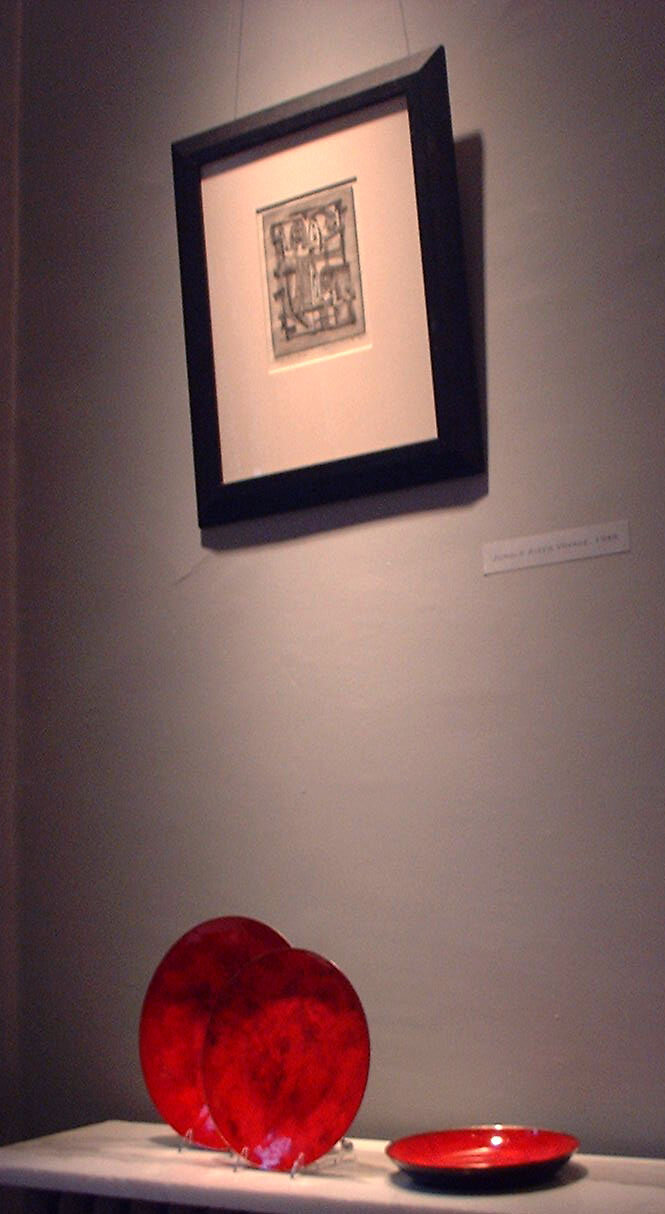

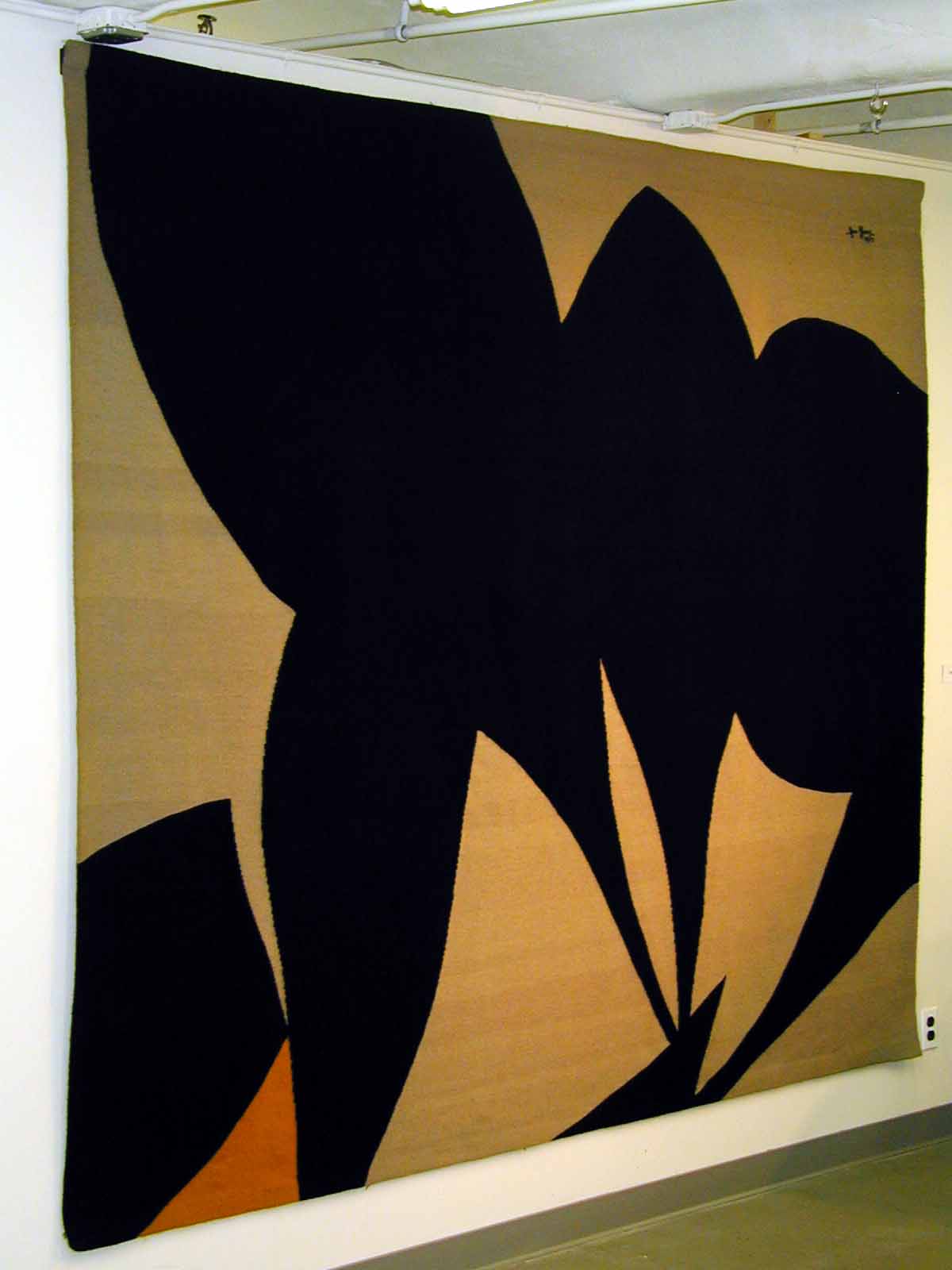

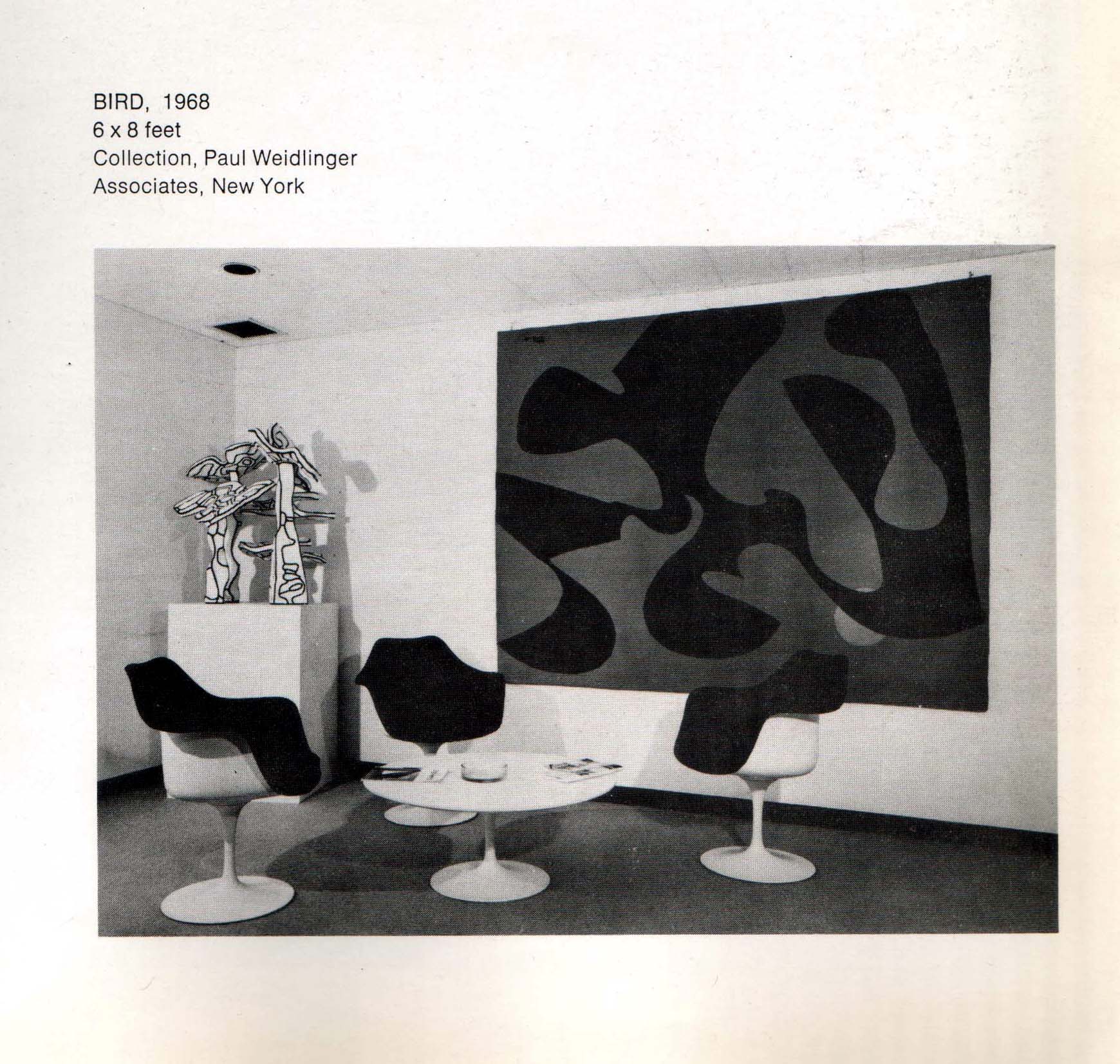

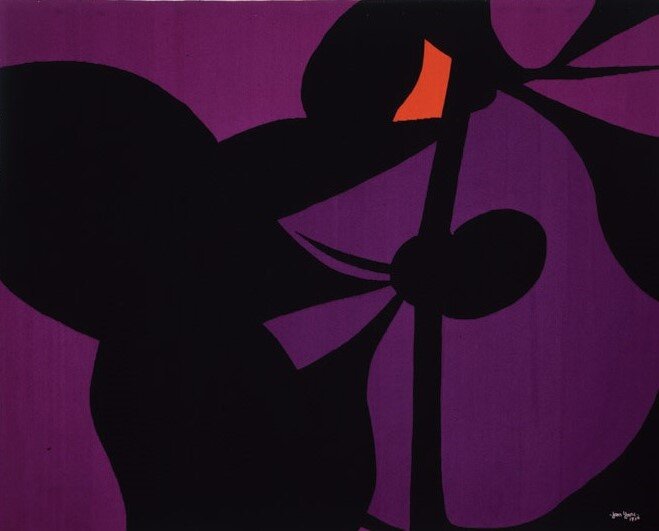

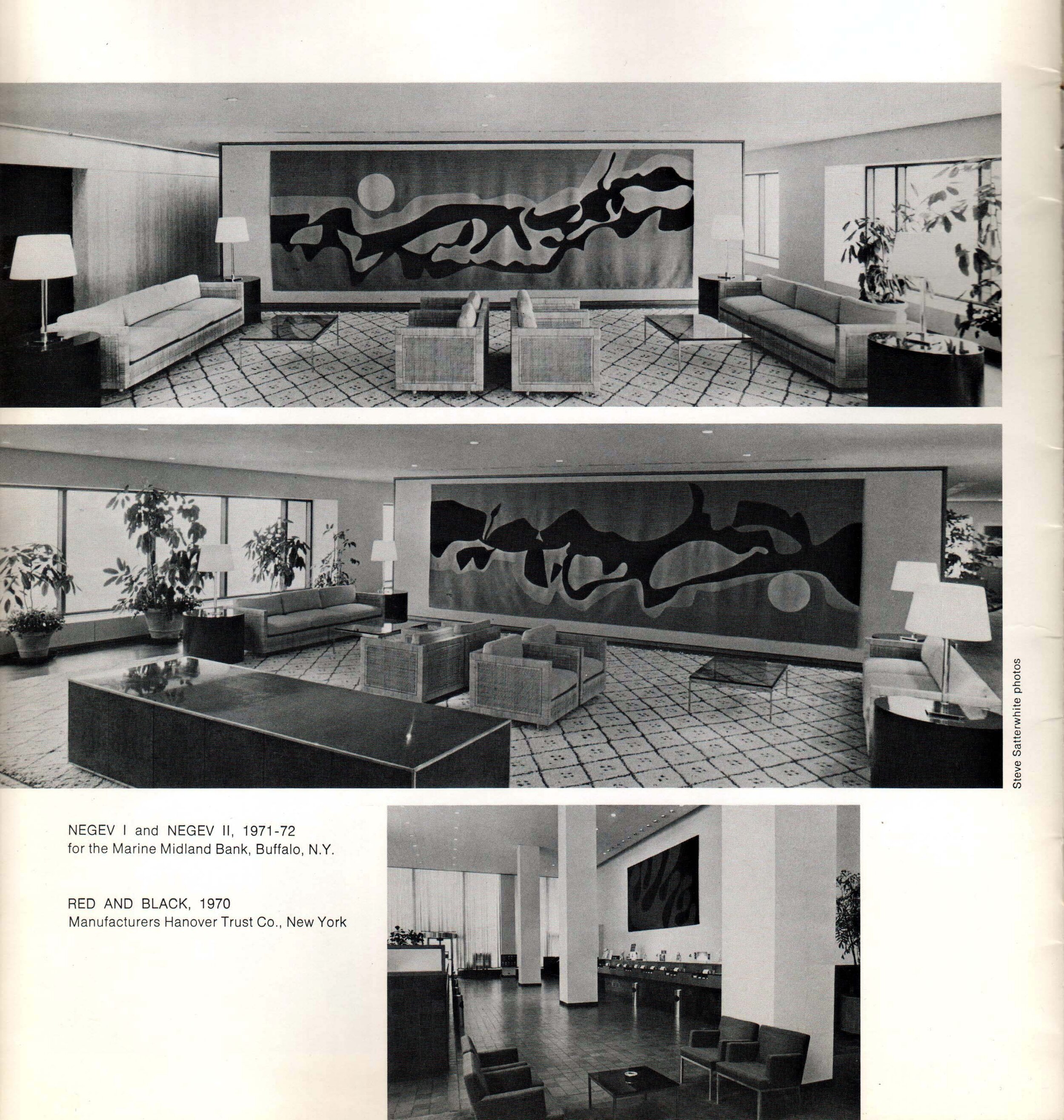

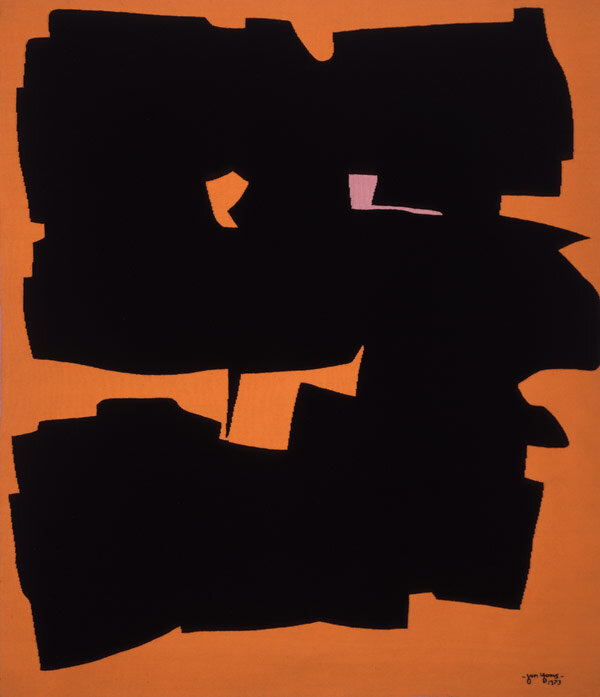

Philadelphia’s Moderne Gallery is presenting an exhibition from June to September 2021 that examines the unique artistic legacy of Paul Hultberg, the first large-scale exhibition of work by this multi-disciplinary artist since his death at 93 in 2019. A once celebrated contributor to the Studio Craft movement, in recent years Hultberg has been attracting renewed recognition as one of the most progressive artists working in enamel on metal in the mid-twentieth century. While he originally trained as a painter, Hultberg began experimenting with enamels in the 1950s, eventually developing his own abstract style that paralleled what many of his peers were doing with paint and canvas in this period. Over the following decades, Hultberg mastered and then revolutionised enameling techniques and became renowned for his large-scale architectural and public works. Rediscovering Paul Hultberg (1926-2019): Abstract Expressionism in Enamel shows both the artist’s early work in vitreous enamel on copper as well as later works in porcelain enamel on steel; view and read more at Moderne Gallery’s website: https://modernegallery.com/rediscovering-paul-hultberg-1926-2019-abstract-expressionism-in-enamel/

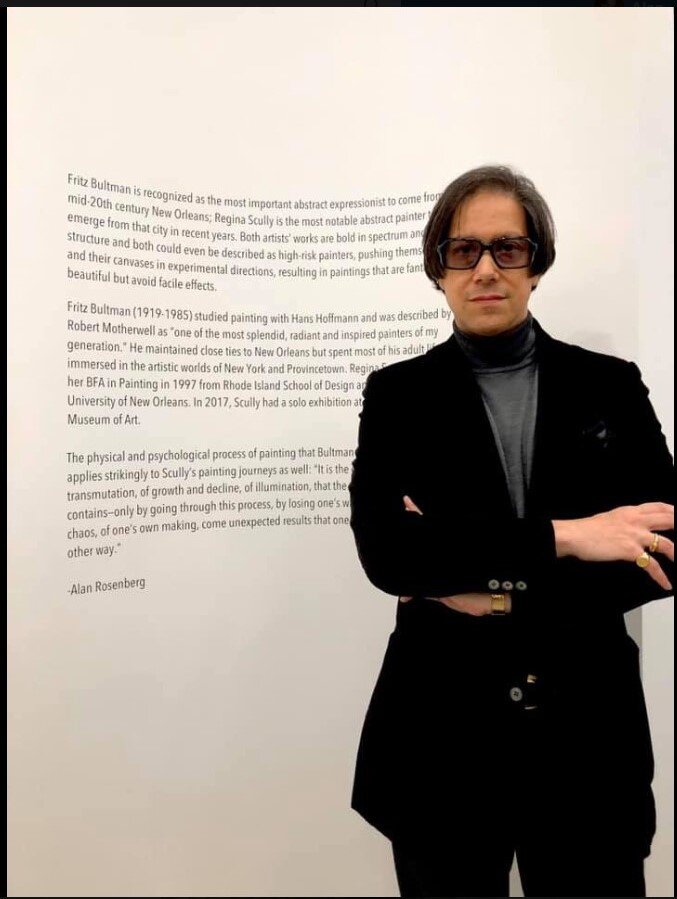

The gallery has published an in-depth catalogue of the works shown which includes essays about Hultberg’s life and works from design scholar Alan Rosenberg and curator and writer Glenn Adamason. In his essay Alan Rosenberg writes that

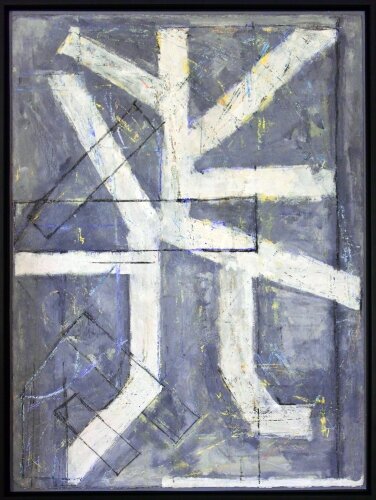

Enamel has been known since antiquity and its appeal, then and now, lay in its rich visual and tactile qualities: its jewel-like colors and glossy-smooth surface. Paul Hultberg (1926-2019) took this traditional craft medium and spread enamel broadly and even brashly over wide fields of copper and steel, just as his abstract expressionist peers did in paint on canvas. Where once it was delicate, Hultberg made enamel bold. Enamel had traditionally reflected light in its mirror-like surface: Hultberg played smooth against rough surfaces in planes that glisten with explosive color, but also absorb and exude darkness like a celestial black hole.

Rosenberg concludes by observing that “Paul Hultberg lives forever in his art, and enamel is much like life: paradoxically fragile and easily broken if mishandled but durable and very long-lasting when treated well.”

View the entire catalogue here.