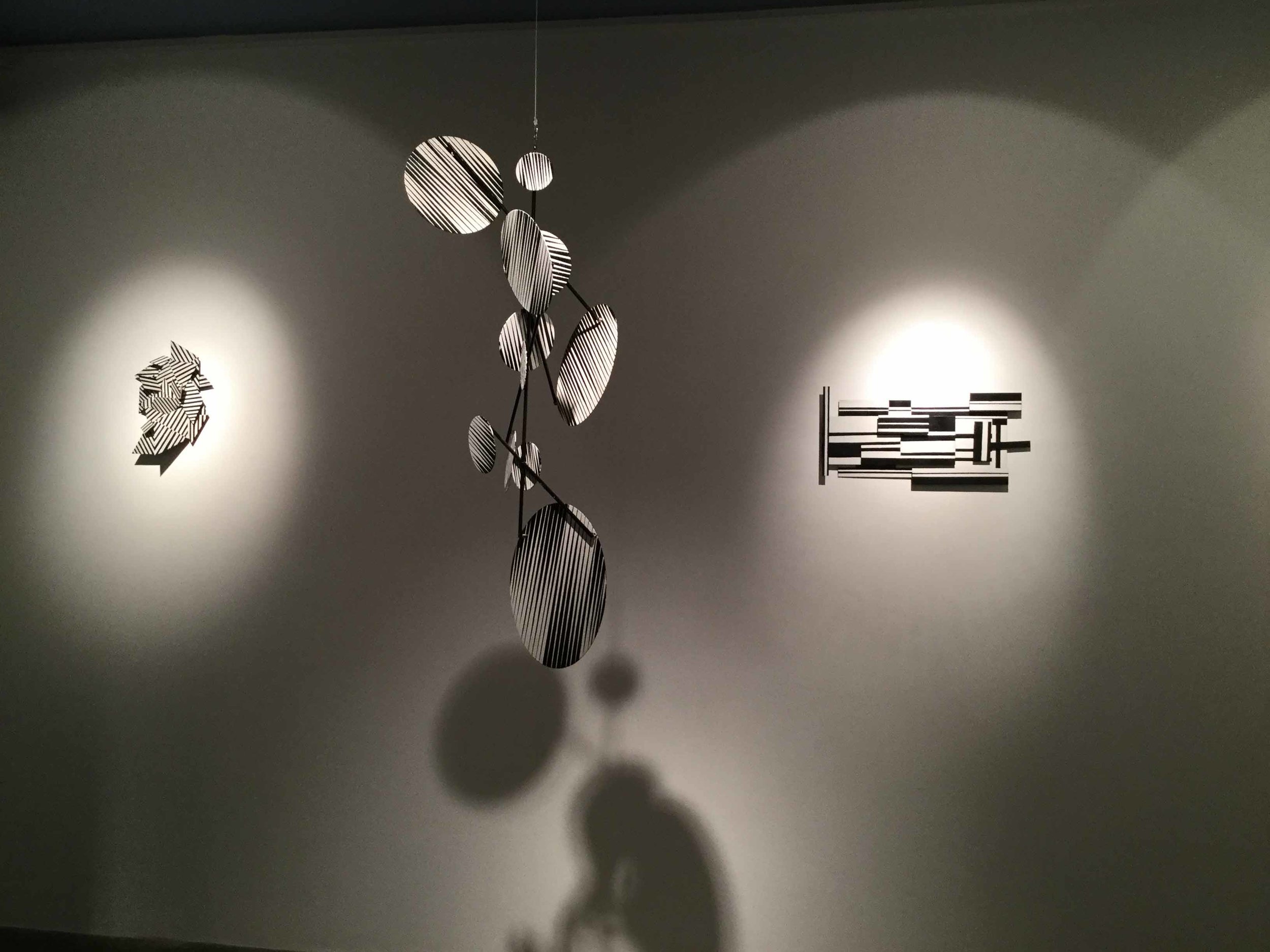

Layla D’Angelo’s new art works on view at Galeria H2O in Barcelona offer an invitation to the infinite. Hints of Russian constructivism, op art and kinetic sculpture are combined in black and white wall mounted iron constructions, held together with magnets, that can be subjected to unlimited reconstruction by the viewer. Fragmentary flat iron pieces suggest diamonds, lozenges, fishscales or jigsaw puzzle pieces, the composite form of which is never final, never reaching conclusion. The image of the chess or checkers board is present in works that are an invitation to play: move the game pieces and plot your next move.

A closer look at the surface of the iron pieces reveals painstakingly applied minute dots of non-color which are revealed to be nail polish. The sculptures have the appearance of pure abstractions but the artist’s use of nail polish as paint give them a literal coating of post-feminist critique. Their resemblance to exploded patchwork quilts and use of a raw material of feminine allure suggest a subtle and simultaneous critique and celebration of women’s work and beauty culture. D’Angelo’s play on femininitude is seen in works that appear as concentric circles, evoking the mystique of the female physical void and the feminine psychic vortex. The constructions’ fragmentation and mutability stand in opposition to the classical monolith, associated art historically with the male presence.

D’Angelo’s corner mounted works echo the Russian constructivist’s engagement of this previously overlooked placement: Vladimir Tatlin’s 1914 “Corner Counter-Relief” and the 1915 Petrograd exhibition of Suprematist paintings by Kazimir Malevich in which his black and white geometric canvases took on three-dimensional form through oblique mounting at the meeting of walls and ceiling. Echoes of mid-20th century Latin-American neo-constructivism are present as well: the astute observer will notice a nod to Lygia Clark’s relational objects and flexible sculptures of the 1950s and 60s. Even the most uninformed art viewer will recognize D’Angelo’s quotation of ultimate Op artist Bridget Riley’s stripes and spirals. Historical antecedents are apparent, but D’Angelo is not a theorist or an academic. A life devoted to creativity, beauty and pleasure has brought her art to the place it occupies today.

Rosalind Krauss observed that in constructivist theory art was seen as "an investigatory tool in the service of knowledge." What knowledge is d’Angelo seeking to convey? Is there even any objective truth to convey? The title of one piece, “Chequered Life,” and it’s mutable form suggest that there is no objective truth but instead there is only subjective experience: life is open ended and art is what you make of it, literally. In this sense D’Angelo’s constructions are Dionysean rather than Appolonian. They are on the side of subjective play, chance and the irrational rather than objective truth and enlightenment. They are subjects not objects: they are constantly subject to the absolute control of the viewer. -©Alan Rosenberg